Allianz Global Corporate Solutions is the reinsurer of the megascraper. Of the 100 tallest buildings in the world, Allianz insurers every single one of them. This has become a defined specialty for them, but there are still plenty of skyscrapers below 100 stories that need coverage, and that are well tall enough to entail many of the same considerations of their taller brethren when it comes to construction and underwriting.

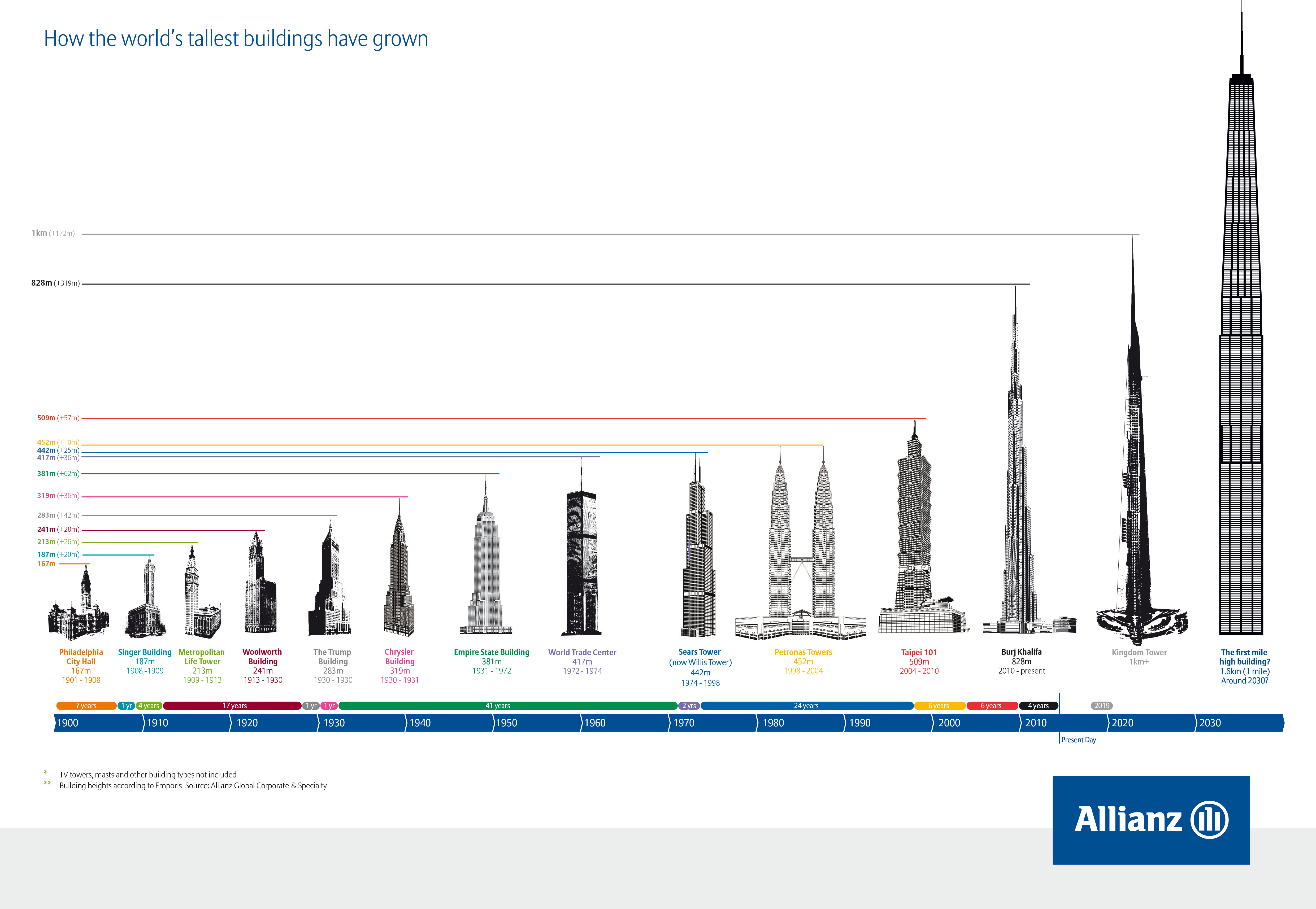

As AGCS has released its report, “Supertall Buldings,: Construction Risk Assessment in the 21st Century,” it covers many of the particular challenges and opportunities of covering such monumental building projects. We have focused on just four of the most important. We will provide a link to the report at the end of this story. (For a closer look at the following graphic – and we suggest that you do, because it is fascinating – click here to see a hi-res version.)

Recommended For You

Want to continue reading?

Become a Free PropertyCasualty360 Digital Reader

Your access to unlimited PropertyCasualty360 content isn’t changing.

Once you are an ALM digital member, you’ll receive:

- Breaking insurance news and analysis, on-site and via our newsletters and custom alerts

- Weekly Insurance Speak podcast featuring exclusive interviews with industry leaders

- Educational webcasts, white papers, and ebooks from industry thought leaders

- Critical converage of the employee benefits and financial advisory markets on our other ALM sites, BenefitsPRO and ThinkAdvisor

Already have an account? Sign In Now

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.