The Ward Agency is a small firm on the Jersey shore that mostly offers personal lines coverage, as well as some business insurance and even financial planning. It is also just a block away from the beach on Ocean Avenue, in Point Pleasant Beach, N.J. But since the main office is on 10-foot-pilings, when Superstorm Sandy hit, the agency escaped damage. There was no power, and the agents had to work from their boss' house, but the agency itself was untouched.

The Ward Agency is a small firm on the Jersey shore that mostly offers personal lines coverage, as well as some business insurance and even financial planning. It is also just a block away from the beach on Ocean Avenue, in Point Pleasant Beach, N.J. But since the main office is on 10-foot-pilings, when Superstorm Sandy hit, the agency escaped damage. There was no power, and the agents had to work from their boss' house, but the agency itself was untouched.

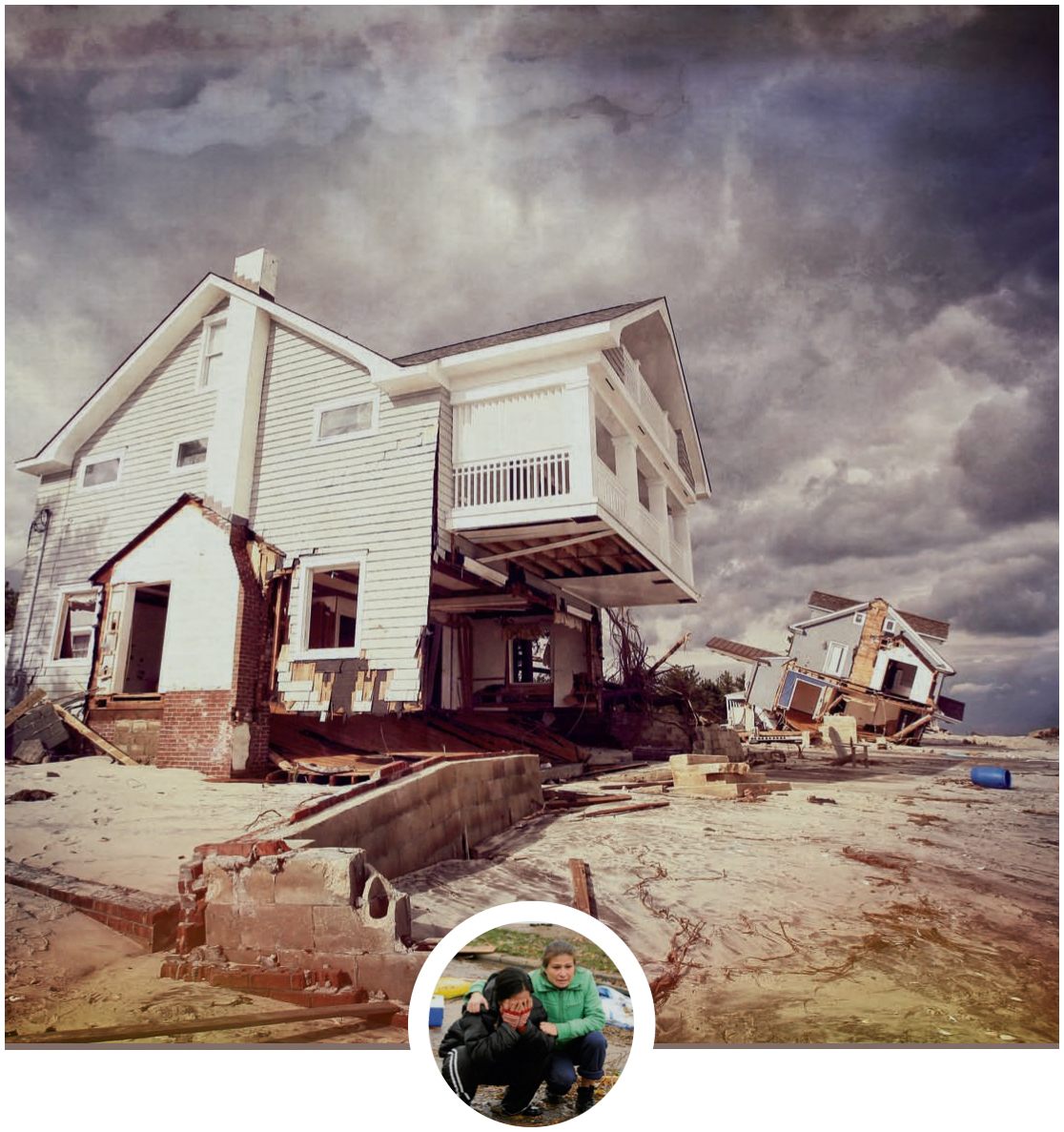

A lot of their neighbors, however, were not so fortunate, and suffered serious flood damage that in many cases remains unresolved even a year after the storm.

“I know they say 90-something percent of flood claims are closed but that's just not right,” says Wendy Audino, a producer for the Ward Agency. She says homeowners have received a check from the National Flood Insurance Program, but by no means is the claim “closed.”

Recommended For You

Want to continue reading?

Become a Free PropertyCasualty360 Digital Reader

Your access to unlimited PropertyCasualty360 content isn’t changing.

Once you are an ALM digital member, you’ll receive:

- Breaking insurance news and analysis, on-site and via our newsletters and custom alerts

- Weekly Insurance Speak podcast featuring exclusive interviews with industry leaders

- Educational webcasts, white papers, and ebooks from industry thought leaders

- Critical converage of the employee benefits and financial advisory markets on our other ALM sites, BenefitsPRO and ThinkAdvisor

Already have an account? Sign In Now

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.