Adriann Conigatti is angry.

Adriann Conigatti is angry.

A Staten Island resident and mother of three, she's a sharp, middle-class working woman in her early 40s who, along with her husband Rob, now finds herself in a tight spot one year after Superstorm Sandy. Not unlike many residents of Richmond County, she feels that the insurance industry has failed her.

The night Sandy swept through Staten Island, dealing an unprecedented level of destruction, the Conigatti family hunkered down on the second floor of their house on Seaver Avenue about a mile from the water's edge of the Atlantic Ocean. The approaching storm surge of water, wrought by winds that reached speeds of 85 mph, “looked like a little tsunami, it was coming and taking cars in seconds,” she recalls. “It just tossed them around.”

As many Staten Islanders did that night, the Conigattis decided to ride out the storm—a decision they lived to regret. The surge swept in but never ended, creeping around their home and through any crevice it could find. Adriann, Rob and their three children, Cassandra, 12; Caterina, 8; and Robert, 5, headed for the second floor and hoped the water would stop.

It didn't. The sliding glass doors on the back porch blew in from the force of the water, shattering with a blast of pressure. By 2 a.m., the waters had burst inside and risen so high that they came within an inch of the second floor—at nearly 9 feet.

“From 8 to 2 we just kept praying,” she says. “I was just resigned to the fact that we were stuck there until morning.” But when a neighbor directed a Boy Scout rescue rowboat to their house, the terrified family escaped—along with three cats in one carrier—and didn't look back.

Their lives, and those of every Staten Islander who lived through Sandy, would never be the same.

THE NIGHTMARE

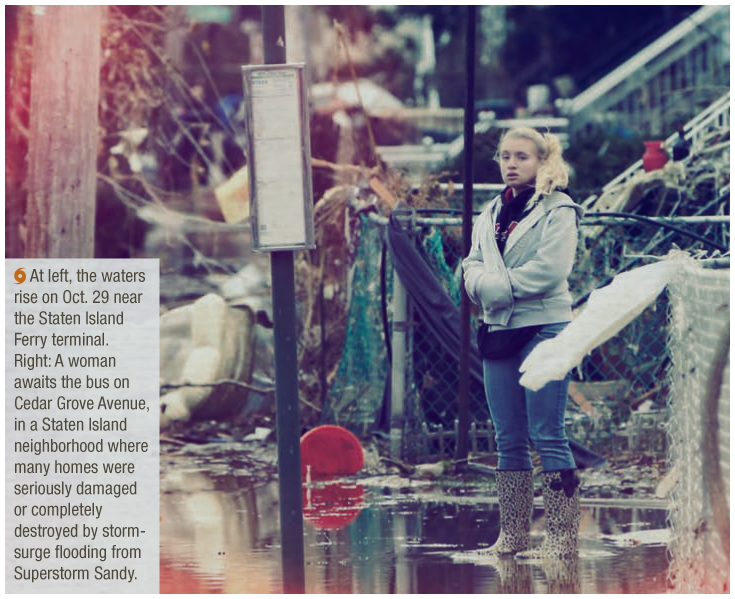

That night, Sandy dealt Staten Island a blow the likes of which it has never seen. Towns like Oakwood Beach, South Beach and Tottenville, all ocean-facing communities, were inundated blocks inland by waves that engulfed houses and killed residents, many of them senior citizens, who ignored orders to evacuate. Hundreds of families were forced from their flooded homes.

That night, Sandy dealt Staten Island a blow the likes of which it has never seen. Towns like Oakwood Beach, South Beach and Tottenville, all ocean-facing communities, were inundated blocks inland by waves that engulfed houses and killed residents, many of them senior citizens, who ignored orders to evacuate. Hundreds of families were forced from their flooded homes.

David Haggerty, 74, and his sister, Charlotte Brewster, 65, drowned when the storm surge forced its way inside their Midland Beach bungalow. As the storm surge approached their Mills Avenue house, Andrew and Angela Sammarco rushed into their basement to fetch their laptop computers from a home office and escape. But water too quickly filled their South Beach basement, separating the couple and trapping 61-year-old Andrew behind a door. His wife, who was on the other side of the door and near the stairway out, could only watch helplessly before she was pulled out by firefighters.

John Filipowicz, 51, a bus driver, and John Jr., 20, were found in their basement at 72 Fox Beach Ave., locked in a final father-and-son embrace. They appeared to have been crushed by debris inside the basement, police said.

Others fled on foot, their cars washed away by the raging waters. In one such chilling, tragic incident that many residents recounted for days, Connor and Brandon Moore, aged 4 and 2, were swept away from their mother when the tidal surge overwhelmed her SUV. Police found their bodies in a marsh off a dead-end road the next day, about 15 yards apart.

By the time the deafening winds had ceased and first light pulled back the curtain on the swath of its destruction, Superstorm Sandy had taken the lives of 24 Staten Islanders.

By the time the deafening winds had ceased and first light pulled back the curtain on the swath of its destruction, Superstorm Sandy had taken the lives of 24 Staten Islanders.

The next morning, the borough lay silent, its residents shell-shocked. Cell phone service was nearly nonexistent; the vast majority of residents had no electricity. Power lines were strewn across Island streets. With no power, the information blackout was widespread; neighbors traded stories they'd heard of people who had perished in their homes, trapped by the waters they thought could never touch them. Only, sadly, many of those tales proved true.

At fuel stations, lines formed almost instantly by those seeking gasoline to power generators. In a borough where driving is the preferred—and best—means of transportation, panicked residents lined up in desperate hope of filling their tanks as word spread that gas was in short supply.

And with so much lost by so many, the policy claims began to roll in.

THE AWAKENING

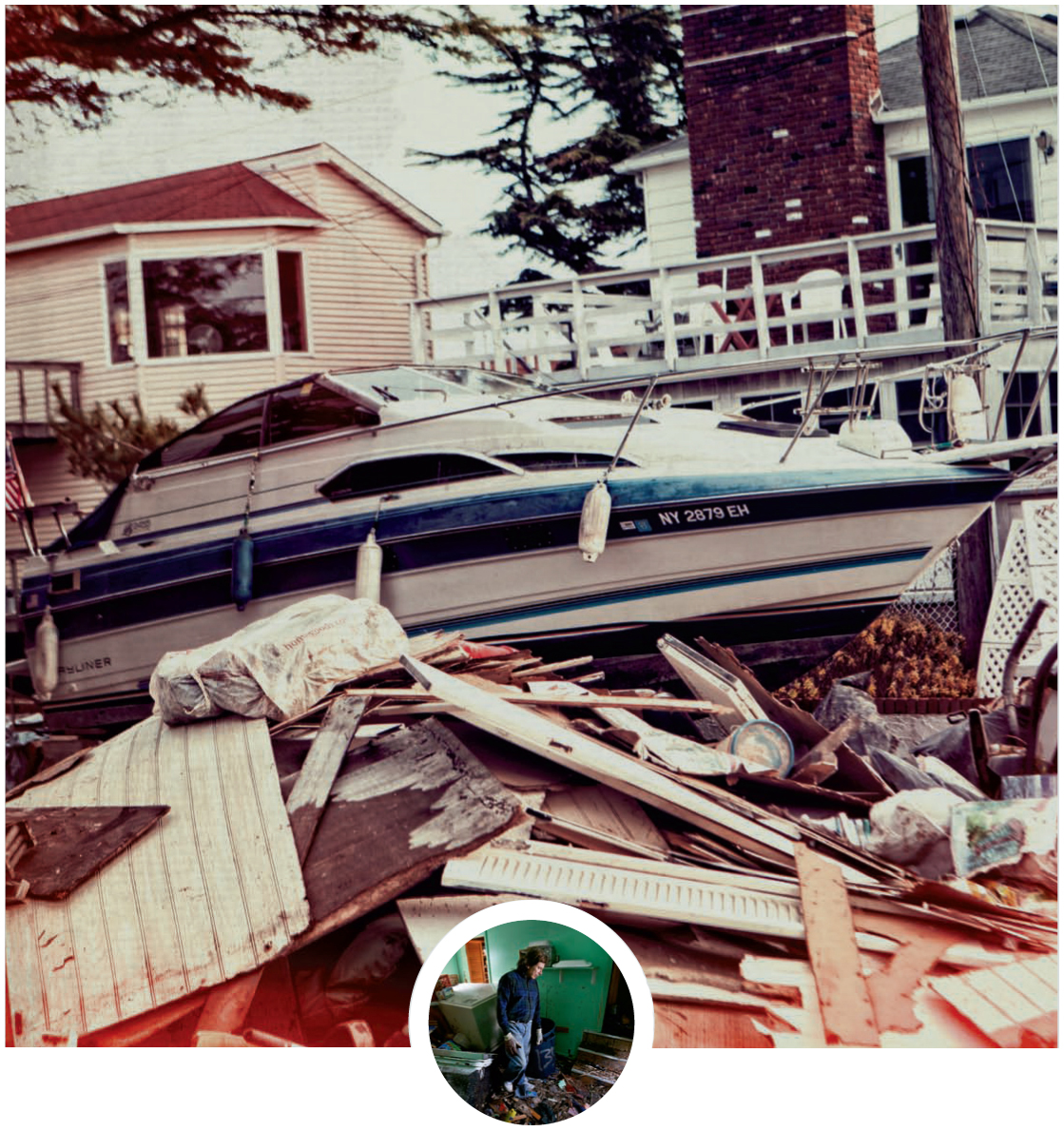

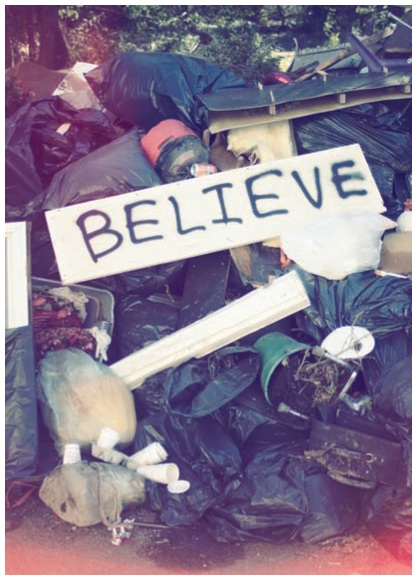

On Nov. 1, the Conigattis were able to return to their home. Just a few towns away in Midland Beach, residents had already began the heartbreaking process of clearing out their homes, all their possessions now amounting to 8-foot heaps of trash awaiting pickup. In some neighborhoods, rows of houses showed this same scene.

On Nov. 1, the Conigattis were able to return to their home. Just a few towns away in Midland Beach, residents had already began the heartbreaking process of clearing out their homes, all their possessions now amounting to 8-foot heaps of trash awaiting pickup. In some neighborhoods, rows of houses showed this same scene.

Adriann knew what she'd likely find. “At that point we were just wondering what was left,” she says, and when they walked in, what they discovered was every bit as bad as she expected. The entire first floor of their home had been wiped out, its contents ruined. They knew the first floor would have to be gutted “down to the sticks,” in contractor-speak. Sump pumps had failed, spewing sewage—another all-too-common lament in Island homes besieged by the storm.

Still, she wasn't that worried. For years, the Conigattis had maintained flood cover, including a contents rider, on their home; Adriann has known her agent since she received her driver's license and purchased her first auto policy, and bundles her coverage.

She reached out to her carrier, and in the meantime hired a private adjuster, a friend of a friend, to have a look around her saturated property and handle the claim. He was optimistic that things would be expedited fairly, if not quickly. With hundreds of others filing claims simultaneously, those with total losses—the true hard cases—would likely be resolved first. And everyone on Staten Island who had a claim knew there was someone else worse off than they were.

“We thought we were going to be OK,” she says.

Three weeks later, an Allstate adjuster arrived, made his own assessment, and delivered the news.

The Conigattis' first floor had been classified as a basement, because to enter the first floor, it's one step down. The outer walls, which are cement, are part of the foundation. Two strikes.

“It was an awakening,” says Adriann. “For years I paid my flood premiums—no one in the neighborhood had coverage like I did. But once they consider you a basement, contents are off the table.”

Her insurer paid out on her heating unit, hot water heater and washer & dryer, all at pro-rated amounts. Sheet rock would be included to help replace the walls, but the cost of taping them was out. The windows were a fight as well, she said, an argument she eventually won. “And then you find out that flood [insurance] also doesn't cover things that are outside, like the shed and the fence, which makes no sense to me; a flood happens outside.”

All told, the Conigattis' settlement fell far short of the cost of the damages, which had been estimated at more than $100,000.

All told, the Conigattis' settlement fell far short of the cost of the damages, which had been estimated at more than $100,000.

At this point, the family faced the same option many other Staten Islanders had: a federal Small Business Administration loan. At around 3 percent interest (a reasonably favorable rate), the Conigattis felt they had little choice if they wanted to start repairs on their home and return their lives to something approaching normalcy. At the time, any federal aid or other grants just couldn't be guaranteed.

The stress of maxing out their credit cards just to begin the work was too much. “You're depleting your savings to get your heat and electric back on,” she says. “I have three kids; you want to get back in your house so that they have a place to live.”

So they applied, were accepted, and borrowed $72,000 over 30 years. But complications remained. As is the case with FEMA grants, the SBA loans require the lendee to carry flood insurance. The Conigattis' policy recently came up for renewal, and the post-Sandy premiums have quadrupled. But they have no choice, even though finances are tight for this typical Staten Island middle-class family. Simply put, they can pay for the insurance or they can sell their house.

“It's so frustrating,” Adriann says. “You think you're doing the right thing all these years. We've been lucky enough never to need benefits through the government or unemployment, or anything, and when you do need help you find out from your insurer that you're not eligible.

“A part of you gets jaded,” she adds. “Until something happens, that's when you really find out what you're covered for.”

THE OUT-OF-TOWNERS

At the Limeri Insurance Agency in the Staten Island town of Great Kills, all Sandy claims have been closed for about two months now, nearly a year after the superstorm. Fred Limeri, an independent agent and the agency's proprietor, says out-of-town adjusters were brought in out of necessity to process the mounting claims proved troublesome in some cases.

At the Limeri Insurance Agency in the Staten Island town of Great Kills, all Sandy claims have been closed for about two months now, nearly a year after the superstorm. Fred Limeri, an independent agent and the agency's proprietor, says out-of-town adjusters were brought in out of necessity to process the mounting claims proved troublesome in some cases.

“Adjusters from Kentucky, Missouri or Idaho don't have the same appreciation of New York property,” he says, noting that a house that would be valued at $80-$90K where they came from is, in many cases, worth twice as much here on half as much land. “You see some assessments and you just go, 'That can't be right.'

“I told my clients, 'If you feel that [the assessment is] off, give me some proof where you think it's off and we'll fight the claims, and we did.”

Still, he adds, the complaints he saw that received high visibility via social media in the weeks after Sandy were the result of people who either at best just didn't care to know what protections their policies included, or, at worst, did know and decided to roll the dice and not carry certain types of cover—and lost.

“You see a lot of postings on Facebook that say, 'I've been insured with this carrier for how many years and I only got $136.' Now, did they think they had flood insurance and really just had a homeowner's policy? I just can't believe that would happen.

“I've been in this business for 40 years,” he adds. “I try to educate people. Do you understand what the differences are in types of coverage? Do you understand no-fault laws?”

Many local businesses on Staten Island were among those who gambled on their coverage and came up broke. On Midland Avenue, long a stretch lined with small businesses, only half of them at best have re-opened.

Those types of coverage decisions, Limeri notes, are not always necessarily made out of frugality, but practicality.

“All they're concerned about is cost,” he says of small businesses when discussing business interruption cover. “Just about all of them want it when you explain to them why it's important, but many feel it's just an expense that they don't want to take on. They may realize it's not the right thing to do, but they're more concerned about payroll and putting food on the table than what happens two years from now.”

Sandy's economic impact could be felt by Island businesses for the next several years, says Dean Balsamini, director of Staten Island's Small Business Development Center. His office dealt with 250 small businesses affected by Sandy to varying degrees, some of them devastated. Some have recovered, like Scaran oil & heating, whose offices were destroyed; and Nunzio's pizzeria, a restaurant that some thought would never re-open after being submerged for days. Others weren't as fortunate.

“We still have some major challenges,” Balsamini says. “The new jobs being created aren't the highest-paying. But we have an increasing immigrant population that is looking to become entrepreneurs—and we have a sizable health care industry here.”

The face of Staten Island is changing a bit, he adds, “for some cases good and other cases not so good,” but one thing is certain: Staten Island is now on notice for its next major hurricane, and the stakes for another recovery are high. “It's not just once a century anymore. That's been made loud and clear.”

THE FORGOTTEN

Sometimes jokingly referred to as “the forgotten borough” (so much so that it actually voted to secede from the city in 1993, an action defused by newly elected Mayor Rudy Giuliani), Staten Island is a borough of middle-class, hardworking people that maintains a distinct small-town feel, despite its population of more than 478,000 at last count.

As New Yorkers, they are practical, proud and pull together in times of need, and Sandy was no exception. When Vivian Norman, a longtime resident of Dongan Hills, found her home to be yet another claimed by the storm, her family and neighbors rallied to help.

While she experienced little agony in dealing with her insurer and was lucky enough to receive a FEMA grant after her daughter, Sally, spent weeks on the phone, she recalls, it was the outpouring of support from those closest to her that helped restore her home. Her experience is a microcosm of how Island residents coped in the aftermath.

“It shined through everything we went through,” she says. “If you needed food, blankets, clothes, water, it was there. Everybody rallied.” Her neighbors bartered for each other's services; one tackled the task of tiling her new bathroom. Electricians traded favors with plumbers.

And now, those residents are skeptical of any outside help being offered to them. This year, only about a third of those eligible for assistance from the federal government applied for it, due to disinterest, cynicism or both.

Case in point: NYC Build it Back offers hundreds of thousands of dollars in aid. Through Community Development Block Grants, residents can sign up for an assessment, and depending upon their eligibility, can have their home repaired and/or elevated; they could have an elevated home built from scratch on their property; or they could have their property acquired by the city to be redeveloped, at post-storm value.

Local politicians have resorted to going door to door in some of the hardest-hit areas, trying to encourage them to apply. Yet since June, only 3,000 Staten Islanders have taken advantage of it—about half of the number the city has estimated are eligible for help.

Many Islanders feel they won't get a cent, and are blunt in telling politicians that to their faces. Others don't want any more “help” from outsiders, thanks very much; they remember all too well how the Red Cross and FEMA trucks, set up in devastated Midland beach, were closed the day one inch of snow fell, just days after they set up shop.

Some, like Adriann Conigatti, are simply uninformed about exactly what the program offers. When it's mentioned to her, she derides it at first—but upon NU's insistence, she reluctantly agrees to investigate it further by the end of our conversation.

Others just want to get on with their lives and put the horrors of Sandy behind them. These are time-strapped, working families who, in many cases, tend to grieve all too briefly and just get on with it.

Indeed, many Staten Islanders, unfortunately, are going to forget about Sandy, says Limeri. “They forgot about Irene already, and that was only a year before.”

His advice, then?

“Don't forget,” he says. He pauses, gathering himself to continue. “Don't ever forget, 'cause once we forget, we lose our direction. Meet with your agent. Go over your coverage, understand your coverage. Then you know you'll be properly protected. Then you won't be so concerned with the cost as opposed to what you're actually getting.”

Want to continue reading?

Become a Free PropertyCasualty360 Digital Reader

Your access to unlimited PropertyCasualty360 content isn’t changing.

Once you are an ALM digital member, you’ll receive:

- Breaking insurance news and analysis, on-site and via our newsletters and custom alerts

- Weekly Insurance Speak podcast featuring exclusive interviews with industry leaders

- Educational webcasts, white papers, and ebooks from industry thought leaders

- Critical converage of the employee benefits and financial advisory markets on our other ALM sites, BenefitsPRO and ThinkAdvisor

Already have an account? Sign In Now

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.