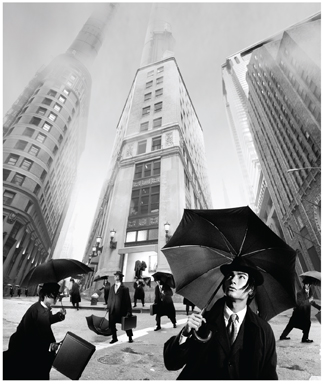

This may be a very good decade to be a catastrophe adjuster. At least, such men and women will apparently be fully employed. Claims ranging from the Deepwater Horizon oil spill in 2010 to the blizzards this past winter and the tornadoes in the spring—estimated at an insured loss of $2.5 billion—and the flooding in the Red River and Lower Mississippi basin, from Missouri to Louisiana, loss, insured, and otherwise, will cause gray hair in the underwriting departments and fatter wallets in the independent claims industry.

This may be a very good decade to be a catastrophe adjuster. At least, such men and women will apparently be fully employed. Claims ranging from the Deepwater Horizon oil spill in 2010 to the blizzards this past winter and the tornadoes in the spring—estimated at an insured loss of $2.5 billion—and the flooding in the Red River and Lower Mississippi basin, from Missouri to Louisiana, loss, insured, and otherwise, will cause gray hair in the underwriting departments and fatter wallets in the independent claims industry.

Who would have dreamt the mess Mother Nature would inflict in this year's annual tizzy? Drought in the West, tsunamis in California, wildfires in Texas, floods in the North and South, and powerful windstorms, accompanied by vicious hail, from Oklahoma to New York.

What will be next? Some religious groups had predicted the end of the world by May 21, but those thoughts are being reconsidered. They cited all the catastrophic situations emphasized by global media networks, where we first hear about disasters. Krakatoa's explosion and tsunami in 1883 was the first such major disaster to gain worldwide attention due to the invention of the underwater telegraph line. Before that, such an event would simply have been considered some South Seas tall tale. So, what is coming? We have already experienced a very hot summer and are in the middle of an active hurricane season.

Recommended For You

Want to continue reading?

Become a Free PropertyCasualty360 Digital Reader

Your access to unlimited PropertyCasualty360 content isn’t changing.

Once you are an ALM digital member, you’ll receive:

- Breaking insurance news and analysis, on-site and via our newsletters and custom alerts

- Weekly Insurance Speak podcast featuring exclusive interviews with industry leaders

- Educational webcasts, white papers, and ebooks from industry thought leaders

- Critical converage of the employee benefits and financial advisory markets on our other ALM sites, BenefitsPRO and ThinkAdvisor

Already have an account? Sign In Now

© Touchpoint Markets, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more inforrmation visit Asset & Logo Licensing.