There is an old folk tale about two frogs: One lives on the edge of a deep, secluded pond. The other lives on the edge of a shallow pond near a country road. The first frog exhorts his friend to relocate; if he stays in that shallow pond, bad things will happen. But that second frog stays because he is afraid to abandon what he knows—however uncomfortable or unsustainable it might be—for the unknown.

Soon after, disaster befalls the frog of the shallow pond. In Aesop's telling, a wagon comes by and crushes the frog. In another version, the shallow pond dries up, leaving the frog to bake in the sun. And in another version, because the shallow pond is so easy to reach, lots of additional frogs move in, and they soon eat all the flies and collectively starve. The end result is always the same: Those who are unwilling to face change invite self-destruction.

A McKinsey & Co. report in 2013, “Agents of the Future: The Evolution of Property & Casualty Insurance Distribution,” seems to echo this parable. McKinsey identifies the usual suspects that spell supposed doom for any agent or broker selling personal lines insurance: increasing product commoditization; a rise of multichannel distribution (at the expense of traditional walls between older product channels); a desire among customers to buy directly from the carrier—and an increasing willingness of the carrier to accommodate them. “There are signs that the economics of the traditional agent model are beginning to unravel,” McKinsey writes, suggesting that perhaps the personal lines pond had too many frogs and not enough flies.

But is that really the case? Not everyone thinks so.

Chasing the 'Golden Egg'

The Hanover Insurance Group directs a lot of energy toward supporting its exclusively independent agent distribution system, rather than concentrating on selling personal lines directly, as other national carriers might. This gives the company a keen sense of how independent agents are approaching personal lines, says Dick Lavey, executive vice president, president of personal lines and chief marketing officer for The Hanover.

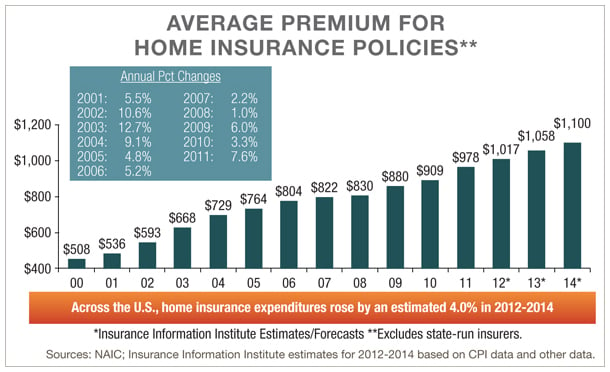

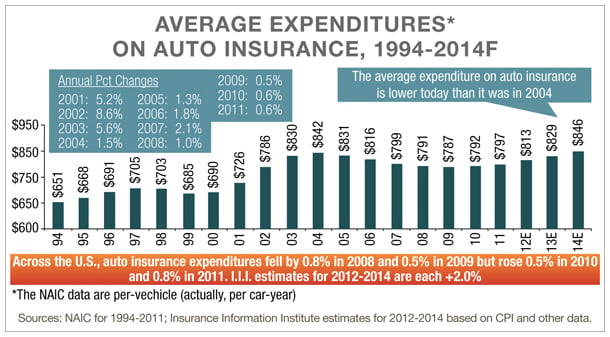

“The whole independent agent channel is thinking more about personal lines than before,” Lavey says, pointing out that on average, commercial lines tend to have a 20% EBITA (earnings before income, taxes and amortization) margin. For personal lines, it is closer to 30% because personal lines is what he calls a “sticky” business. All of the direct-sales efforts in the world won't change the fact that if the average personal Auto or Homeowners policyholder's bill looks pretty much the same as it did last year, most policyholders have little incentive to switch carriers. In many cases, it's just not worth the hassle.

The trick, Lavey says, is to chase what he calls “the golden egg”—the combination of Auto, Homeowners and other personal lines within the same client. The public isn't thrilled about actually buying insurance, however, and price alone won't win the day, so value-added services must be considered—such as phone apps that let you take video inventory of your house and store it on the cloud to speed claims, or services that send recall notifications or make and model news based on your vehicle identification number.

“We're trying to create services the customer wants, to bring Homeowners and Auto together,” says Lavey. “That makes them feel attached both to the carrier and the independent agent who provided it all.”

Not all innovations are pure upside, though, says Gavin Blair, chief product officer for personal lines at The Hanover. Take smart windshields and collision detection, two safety measures that automakers are introducing to help prevent collisions. While Blair hasn't yet seen such things reduce the frequency of accidents, he worries that when there is a loss, it will be more severe. “Those sensors are expensive,” he says. “A minor fender-bender could become a $6,000 event just to fix a camera.”

Blair also notes that the falling price of gasoline isn't likely to help personal Auto, either. As gas gets cheaper, people drive more. Those carriers who only sell personal Auto may see a lot more miles driven, and correspondingly, more accidents.

Blair also notes that the falling price of gasoline isn't likely to help personal Auto, either. As gas gets cheaper, people drive more. Those carriers who only sell personal Auto may see a lot more miles driven, and correspondingly, more accidents.

Telematic devices, like Progressive's Snapshot, which drivers voluntarily plug into their cars to transmit back to their insurers driving data, such as average speed, braking tendencies and sharpness of turn, can be used to price risk more effectively. And in areas such as commercial Trucking, Blair says that the “sentinel effect” of knowing somebody is studying how you drive can impose safer driving habits. But it hasn't caught on in the personal space. The telematic devices themselves cost about $90 each and the cost of data transmission is another $50 to $60 a year, in addition to the cost of shipping the devices out to customers. All this, for Auto policies that on average cost around $1,000 a year. The ROI just isn't quite there yet.

What's more, many people just don't like plugging Big Brother into their cars. Ironically, they are more likely to permit the same transmission of data from their smartphones or wearable tech, Blair says—so until insurers get policyholders to install telematic apps (which he believes could do a lot of good with the teen market), the promise of telematics might not yet be fully realized.

New Dawn for Independents

Brian Cohen, an operating partner at Altamont Capital Partners in Palo Alto, Calif., brushes off the notion that personal Auto—which accounts for some 70% of the total personal lines market, is on an inevitable march toward direct sales and total commoditization. “People point to the U.K. as an example of what should happen here,” Cohen says, referring to how the personal Auto market in the U.K. has gone almost entirely direct, mostly sold through the Internet. But, he adds, that's only because carriers there can change prices at a moment's notice (they don't have to file with America's 50 different Departments of Insurance), and so they can race to the bottom on price.

Agency-based carriers still dominate the personal lines market, Cohen says, and when it comes to using the Internet to drive sales, it's the agents who use it best, employing Constant Contact, Google ads or other digital marketing tools to get their names in front of their local micro-markets where they can sell most effectively. Using real-time raters to produce instant quotes for curious online shoppers—quotes that also direct them to their local agent—further maintain the agent's relevance in a digital world. So much for the comparison of today's insurance distribution to yesterday's travel agents.

Agency-based carriers still dominate the personal lines market, Cohen says, and when it comes to using the Internet to drive sales, it's the agents who use it best, employing Constant Contact, Google ads or other digital marketing tools to get their names in front of their local micro-markets where they can sell most effectively. Using real-time raters to produce instant quotes for curious online shoppers—quotes that also direct them to their local agent—further maintain the agent's relevance in a digital world. So much for the comparison of today's insurance distribution to yesterday's travel agents.

As one example, Cohen points to CompareNow, a direct writer started in the U.S. by U.K. insurer Admiral. “They thought they'd kill it here,” Cohen says. “They got lots of press, but they have had no measurable impact in terms of volume. If you go to their site, it looks great, and you think that this should work. But it just doesn't.”

The other thing to look at, Cohen says, is that all of the pressure in personal lines is really on the captive agents. In a world where consumers expect multiple buying choices for everything, getting a single quote from a single insurer just won't cut it. They expect multiple quotes that the captive agent just can't provide. And they need a professional to advise them on what the trade-offs are when choosing one carrier over another.

What makes things worse for captive agents, Cohen says, is the rise of the agent aggregator, a kind of field-marketing organization that represents several hundred independent agents under a single umbrella, and are very good at seeding Google searches on insurance products with links that lead back to them. According to Cohen, aggregators are luring established, successful agents away from captive insurers with the promise of upside sales potential that comes with access to multiple carriers, while offering them the same kind of support they might have enjoyed within a captive system.

“Aggregators aren't enlarging the pie,” Cohen says, “they're just shifting the most productive agents from the captive to the independent channel. This is new. For several decades, you saw the number of independent agents dropping and captives rising. Now, that is starting to switch.”

Aggregators might be the least of carriers' concerns. Personal lines remains an incredibly competitive market, especially with rock-bottom interest rates giving insurers no choice but to make their money on underwriting profit, which is far easier said than done. Cohen notes that many carriers are writing unprofitable business just to maintain their market share in the face of internecine pricing from competitors. This is especially true where carriers are doing whatever they can to lock in both a customer's personal Auto and Homeowners business, that “golden egg” that Lavey at The Hanover referred to previously.

The good news is that because reinsurance is so incredibly (some would say excessively) abundant right now, insurers can write coverage more cheaply and hedge that extra risk on their books by negotiating very competitive reinsurance treaties. But the challenge remains for personal lines writers to grow profitably, and the key there, Cohen says, is to target niches. That too, isn't easy, because most carriers are already using big data and analytics to identify potentially profitable markets—such as motorcycles, recreational vehicles and light watercraft. For most, the answer to profitable growth might just come down to acquisition.

Homeowners is more of a free-for-all, where big carriers face substantial concentration of risk in coastal areas stretching from Maine to Texas. A lot of them don't really want to write there, Cohen says, which is giving an opportunity to smaller, more aggressive writers who are taking advantage of cheap, plentiful reinsurance to go where angels fear to tread.

A great example of this is California, “which was almost a four-letter word when writing property,” says Cohen, thanks to every kind of anathema to a homeowners book—mudslides, earthquakes, wildfires. But loss data shows that the California property market has actually been profitable for the last 20 years, Cohen adds, which is drawing in aggressive new players to that market.

And it's not like big carriers can trade on their brand recognition. “'Like a good neighbor' doesn't resonate like it did 20 years ago,” Cohen says, thanks to public distrust of big institutions—especially insurance carriers—following the post-2009 financial crisis. This enables smaller, nimble carriers to penetrate markets in ways they never could before—and it gives an independent agent willing to do some homework on those carriers targeting niche markets a competitive advantage over their peers.

“The big headlines are that if you're in personal lines, you're in a dying area of the insurance industry. In fact, you are not,” Cohen says. “If you are an independent agent focusing on personal lines, there are incredible opportunities today that weren't available 10 or 20 years ago. You have to look at your market and your business in a different way than you might have in the past. If you do that, this is the new dawn of the independent agent. If I was entering the industry and thinking about where I would want to be on the distribution side, I would want to be an independent agent.”

Want to continue reading?

Become a Free PropertyCasualty360 Digital Reader

Your access to unlimited PropertyCasualty360 content isn’t changing.

Once you are an ALM digital member, you’ll receive:

- Breaking insurance news and analysis, on-site and via our newsletters and custom alerts

- Weekly Insurance Speak podcast featuring exclusive interviews with industry leaders

- Educational webcasts, white papers, and ebooks from industry thought leaders

- Critical converage of the employee benefits and financial advisory markets on our other ALM sites, BenefitsPRO and ThinkAdvisor

Already have an account? Sign In Now

© 2025 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.